Algonquin Park

Logging of Algonquin's endangered old-growth forests began in the early 1800s and continues to this day

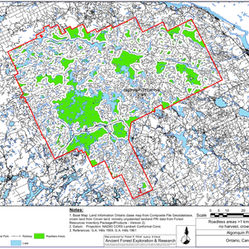

About 60,000 acres (24,000 hectares) of old-growth forest are available for logging within 65% of Algonquin Park. AFER's research in Algonquin Park is therefore focused on locating and documenting these remaining endangered ecosystems.

Over the past two centuries of logging in the Park, 13 species have significantly declined there including: American elm, basswood, black cherry, eastern hemlock, eastern white pine, jack pine, larch/tamarack, northern white cedar, red oak, red pine, red spruce, white ash, and yellow birch (AESL 2010). Habitat declines in Algonquin have had negative impacts on bird species including barred owl, blackburnian warbler, black-throated green warbler, brown creeper, oven bird, parula warbler, red-shouldered hawk, saw-whet owl, whitxe-winged crossbill, and wood thrush (AESL 2010, Geleynse et al. 2015). Additional species impacts due to humans have been documented in Algonquin for wolves (Benson et al. 2015), moose (McLaughlin et al. 2011), beaver (AESL 2010), lake trout (Shuter et al. 2015), gray jays (Derbyshire et al. 2015), bees (Nol et al. 2006, Nardone 2013), hoverflies and click beetles (Nol et al. 2006), and crayfish (Hadley et al. 2015).

Unprotected Old-growth Forest in Algonquin Park

Save Algonquin Old-Growth

A Project to Find and Document Endangered Forests in Algonquin Park

The purpose of AFER's current work in Algonquin Park is two-fold: 1) conduct forest assessments in the field to determine if forest composition mapping for Algonquin's potential old-growth forests is accurate, and 2) describe those unprotected forests that have been confirmed as old-growth with photographs, videos and other field data including ages determined by tree cores where possible. Field reports will be produced for each old-growth landscape that is assessed and will be used to educate the public and advocate for their protection. We will share our results with The Wilderness Committee and Global Forest Watch so that they may use our findings to promote protection of these endangered ecosystems.

AFER’s work in Algonquin Park started in 2006 when Michael Henry was working on the first edition of the book Ontario’s Old-growth Forests. He wanted to understand the significance of the old-growth forests found in the Park so he started by analyzing forest inventory data for the Park and compared it to Province-wide data – the results were surprising! The data showed that Algonquin Park contained 40% of the old-growth forest (>150 years) in central Ontario while occupying only 4% of the land area. At the time, only half of the old-growth forest in the Park was protected – the rest was available for logging in the recreation-utilization zone of the Park. Henry also aged some large trees in the Park finding that some of the unprotected forest had trees over 300 years old.

Between 2007 and 2013 the Province undertook a process called Lightening the Ecological Footprint of Logging in Algonquin Park. In 2013, the Lightening the Footprint recommendations were incorporated into an amendment to the Algonquin Park Management Plan, and as a result the protected area was increased from 22 to 35 percent of the Park. Although our 2006 report was referenced during this process, our recommendation to protect all the old-growth forest remaining in the Park was largely ignored. The additional protected areas that were created in 2013 prioritized recreation by buffering portages and lakes along canoe routes from logging activities.

After this process was completed roughly 24,000 hectares of the oldest forest (>150 years) in Algonquin Park was unprotected at the end of 2018, and our recent field studies show that some of the finest examples of old-growth forest in the Province remain available for logging in Ontario’s oldest provincial park (i.e. trees up to 408 years old in the unprotected forest west of Cayuga Lake. Our studies of old growth in Algonquin continue finding additional old-growth forest areas that will be made public soon.

See MAPS BELOW ON THIS PAGE

Seeking Citizen Scientists and Supporters

We are looking for assistance to identify and characterize unprotected old-growth forests in Algonquin Park. If you are interested, you can help by locating and documenting old-growth forest, making a donation and/or volunteering! If you share our concern for the Algonquin landscape or just want to learn more about this project, we want to hear from you.

Research Highlights

Significant findings from AFER's research in Algonquin Park include:

AFER developed a quantitative model that incorporates the complex fire-soil moisture (combination of precipitation and %sand) gradient as the major influence on upland forest composition in Algonquin Park that can be used to evaluate future fire management and logging impacts on the health of forests in the Park.

Using the scientific literature, AFER assessed the actual and potential influences of climate change on water quality and quantity; species and ecosystems; and resource industries, infrastructure, and human health in the northwestern portion of the Algonquin Region.

AFER was the first to use GIS and regional digital data to map wildlife habitat and ecological connectivity linking Algonquin Park with the Adirondack State Park in New York State.

AFER was the first to use GIS and regional digital data to map wildlife habitat and ecological connectivity linking Algonquin Park with the Temagami Region of Ontario.

AFER has produced the most comprehensive and detailed maps of old-growth forests in Algonquin Park based on digital GIS data available from the provincial government.

AFER produced the only known field study of riparian forests located in Algonquin Park.

AFER has assessed fragmentation from continuing road building (~5,500 km), road use, and forestry activities in Algonquin Park determining that the Park's original, unlogged, native landscape has been reduced to 18% also resulting in the decline of at least 16 species at-risk.

Forest Conservation Achievements

AFER’s research has increased awareness of old-growth forests in Algonquin Park and has influenced several forest conservation publications and activities including the following

Algonquin Wildlands League. Restoring Nature’s Place. Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, Toronto, Ontario.

ArborVitae Environmental Services Ltd. Management of Algonquin Park’s West Side Forests and Provision of Associated Habitat. Report Prepared for Algonquin Eco Watch, Spring Bay, Ontario.

Beier, P., D. R. Majka and S.L. Newell. Uncertainty analysis of least-cost modeling for designing wildlife linkages. Ecological Applications 19:2067-2077.

Beier, P., D. R. Majka and W. D. Spencer. Forks in the Road: Choices in Procedures for Designing Wildland Linkages. Conservation Biology 22:836-851.

Carroll, C. Impacts of Landscape Change on Wolf Viability in the Northeastern U.S. and Southeastern Canada: Implications for Wolf Recovery. Wildlands Project, Special Paper No. 5, Richmond, Vermont.

Carroll, C. Carnivore Restoration in the Northeastern U.S. and Southeastern Canada, A Regional Scale Analysis of Habitat and Population Viability for Wolf, Lynx, and Marten: Lynx and Marten Viability Analysis. Wildlands Project, Special Paper No. 6, Richmond, Vermont.

Guyette, R. P. and D. C. Dey. Age, Size and Regeneration of Old-Growth White Pine at Dividing Lake Nature Reserve Algonquin Park, Ontario. Forest Research Report 131, Queen’s Printer for Ontario, Ontario Forest Research Institute, Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario.

Kingsley, A. and E. Nol. Bird Species Richness and Composition in White Pine (Pinus strobus) Stands in Algonquin Provincial Park, Ontario in Response to the First Cut of the Uniform Shelterwood Silvicultural System. In: Parks and Protected Areas Research in Ontario, Proceedings of the Parks Research Forum of Ontario (PRFO), 1998 Annual General Meeting, Peterborough, Ontario, published by Heritage Resources Centre, University of Waterloo, Ontario.

Langen, T. A. and R. Welsh. Effects of a Problem-Based Learning Approach on Attitude Change and Science and Policy Content Knowledge. Conservation Biology 20: 600-608.

Rushowy, K. 408-year-old tree discovered in Algonquin Park’s unprotected logging zone. Toronto Star, January 12, 2019.

Stephenson, B. The Algonquin to Adirondack Conservation Initiative: A Key Macro-Landscape Linkage in eastern North America. In: Crossing Boundaries in Park Management, Proceedings of the 11th Conference on Research and Resource Management in Parks and Public Lands, ed. by D. Harmon, the George Wright Society, Hancock, Michigan.

Vasarhelyi, C. and V. G. Thomas. Evaluating the capacity of Canadian and American legislation to implement terrestrial protected areas networks. Environmental Science & Policy 9:46-54.

Winkowski, J. J. and M. D. Petrik. Thinking Big, Acting Local: The how’s and why’s of an Adirondack to Algonquin corridor. Department of Biology, St. Lawrence University, prepared for the Conservation Biology Case Study Symposium, Spring 2007.

AFER’s work has also contributed to the creation of the Frontenac Arch Biosphere Reserve and the A2A Algonquin to Adirondacks Collaborative.

Publications

Books & Journal Articles

Book: Ontario's Old Growth Forests (2021)

Journal: Impacts of Logging on Old-growth Eastern White Pine and Red Pine near Algonquin Park (2000)

Journal: A Review of the Selection and Design of the Forested Nature Reserves in Algonquin Park, Ontario (1996)

Journal: An Index to Fire Incidence (1987)

Research Reports

Two Centuries of Logging and Road Building have Fragmented Habitat and Reduced Wilderness to 18% in Algonquin Park, Ontario (RR#48, 2024)

A Field Study to Characterize Riparian Ecosystems in the Northwest Algonquin Region of Ontario (2015)

Riparian Ecology and Restoration in Eastern Canada: A Literature Review (2015)

A Preliminary Survey of Old-growth Forest Landscapes on the West Side of Algonquin Park (2006)

Forest Landscape Baseline Reports

Climate Change in the North Bay-Algonquin Park Region: Effects on Ecosystems and Species (2010)

Mapping Threatened Old-Growth Forests of Algonquin Park: The First Step (2007)

The Temagami-Algonquin Wildlife Corridor (2002)

Status of Old-Growth Red Pine Forests in Eastern North America: A Preliminary Assessment (1996)

A Predictive Model for Upland Forest Community Composition in Algonquin Park, Ontario (1993)

Old-Growth Eastern White Pine Forest: An Endangered Ecosystem (1993)

Preliminary Results Bulletins

The Cayuga Lake Old-Growth Forest Landscape: an Unprotected Endangered Ecosystem in Algonquin Provincial Park, Ontario (2018)

The Hurdman Creek Old-Growth Forest: an Unprotected Endangered Old-Growth Forest in Algonquin Provincial Park, Ontario (2018)

Old Growth Field Notes

Alfred Lake Old Growth Forest: Field Notes No. 1 (Quinby et al. 2018)

Bug Lake Old Growth Forest: Field Notes No. 2 (Quinby et al. 2018)

Manitou Lake Old Growth Forest: Field Notes No. 3 (Quinby and Outward Bound Canada 2020)

Presentations

Opportunities for Wildlife Habitat Connectivity between the Adirondacks and Algonquin Park (2000)

Using GIS and Field Studies to Design a Wildlife Corridor in the Temagami-Algonquin Region of Central Ontario (2003)

Ph.D. Thesis: Vegetation, Environment and Disturbance in the Upland Forested Landscape of Algonquin Park, Ontario, by Peter Quinby, University of Toronto, 1988

Algonquin Upland Forest Ecology (Quinby 1988) - Part 1

Algonquin Upland Forest Ecology (Quinby 1988)- Part 2

Algonquin Upland Forest Ecology (Quinby 1988)- Part3

Algonquin Upland Forest Ecology (Quinby 1988)- Part4

Maps and Resources

References

ArborVitae Environmental Services (AESL). 2010. Management of Algonquin Park West Side Forests. Report Prepared for Algonquin EcoWatch. Georgetown, Ontario.

Benson, J. F. et al. 2015. Resource selection by wolves at dens and rendezvous sites in Algonquin Park, Canada. Biological Conservation 182:223–232.

Derbyshire, R., D. Strickland and D. R. Norris. 2015. Experimental evidence and 43 years of monitoring data show that food limits reproduction in a food-caching passerine. Ecology 96:3005–3015.

Geleynse et al. 2016. Brown Creeper (Certhia americana) demographic response to hardwood forests managed under the selection system. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 46:499–507.

Hadley, K. R. et al. 2015. Altered pH and reduced calcium levels drive near extirpation of native crayfish, Cambarus bartonii, in Algonquin Park, Ontario, Canada. Freshwater Science 34:918–932.

McLoughlin, P. D. et al. 2011. Seasonal shifts in habitat selection of a large herbivore and the influence of human activity. Basic and Applied Ecology 12:654–663.

Nardone. E. 2013. The Bees of Algonquin Park: A Study of their Distribution, their Community Guild Structure, and the Use of Various Sampling Techniques in Logged and Unlogged Hardwood Stands. M.Sc. Thesis, Environmental Biology, University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario.

Nol, E. et al. 2006. The response of syrphids, elaterids and bees to single-tree selection harvesting in Algonquin Provincial Park, Ontario. Canadian Field-Naturalist 120: 15–21.

Shuter, B. J. 2016. Fish life history dynamics: shifts in prey size structure evoke shifts in predator maturation traits. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Science 73:693–708.